With a population exceeding 240 million, Pakistan is no stranger to the fury of nature. Ranked among the top five countries most vulnerable to climate change by the Global Climate Risk Index, Pakistan faces a growing threat from flash floods—sudden surges of water that devastate lives, infrastructure, and economies in minutes.

From the glacial peaks of the Hindu Kush to the arid plains of Sindh, the country’s varied geography makes it exceptionally prone to climate extremes. The deadly flash flood along the Swat River in June 2025, which claimed 18 lives from a single family, is a grim reminder of how climate change is colliding with governance failures to produce preventable tragedies.

Flash Floods in Pakistan

Flash floods in Pakistan are triggered mainly by intense monsoon rains and accelerated glacial melt. The monsoon season (July–September) now often arrives early, while record-breaking heatwaves exacerbate glacial runoff. This perfect storm is intensified by:

-

Steep hills and narrow valleys that channel water into destructive torrents

-

Outdated flood protection infrastructure

-

Less than 5% forest cover, among the lowest in South Asia

-

Rapid urbanization and poor land management

In 2022, floods inundated one-third of the country, killing 1,739 people, displacing 8 million, and causing $40 billion in damages—a disaster the UN dubbed a “monsoon on steroids.”

The Swat Valley, known for its beauty and tourism, has repeatedly suffered—hit by deadly floods in 2010, 2020, 2022, and now again in 2025. The increasing frequency and severity point to a troubling trend.

The Swat River tragedy

On June 27, 2025, a flash flood struck the Swat River near the GE Qurban Hotel on the Swat Bypass, sweeping away 18 members of a family from Sialkot who had stopped to picnic. Children played in the water while others posed for selfies when a surge, triggered by upstream glacial melt and rainfall, turned the calm river into a raging torrent.

By 9:45 AM, water levels reached 77,782 cusecs at Khwazakhela, classified by the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) as a "very high flood situation."

Disturbing videos surfaced showing stranded family members waving for help. Despite the presence of over 120 Rescue 1122 personnel, delays in response meant only three survivors were pulled from the floodwaters. By June 29, 12 bodies had been recovered, one remained missing.

This incident contributed to a nationwide death toll of at least 46, with casualties reported in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (22), Punjab (13), Sindh (7), and Balochistan (4).

The Climate Crisis Behind the Floods

Pakistan contributes less than 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions, yet it faces outsized climate impacts. The Swat River disaster illustrates the deadly convergence of:

Intensifying Monsoons

The Indian Ocean has warmed by 1°C, supercharging monsoon systems. In 2022, rainfall in Sindh and Balochistan was up to 784% above average. The pre-monsoon rains in June 2025, arriving early and fiercely, reflect a disturbing pattern.

Accelerated Glacial Melt

Pakistan’s 13,000+ glaciers are melting rapidly due to rising temperatures. A glacier burst in Kalam Mitaltan—reported by @JN_Araain—was a key trigger for the Swat flooding.

Recurrent Heatwaves

Unrelenting heat in May and June 2025 intensified monsoon rainfall and glacial melt. Similar heatwaves in 2022 created thermal lows that contributed to catastrophic rains.

Deforestation and Land Misuse

Rampant deforestation in the Swat Valley and poor riverbank management have stripped the land of its natural flood defenses, increasing runoff and erosion.

Climate Injustice

As Climate Minister Musadiq Malik stated, this is a “crisis of global injustice.” While rich nations receive 85% of climate financing, Pakistan’s needs—estimated at $40–50 billion annually until 2050—are grossly underfunded. A $1.3 billion IMF climate resilience loan is merely a drop in a rising ocean.

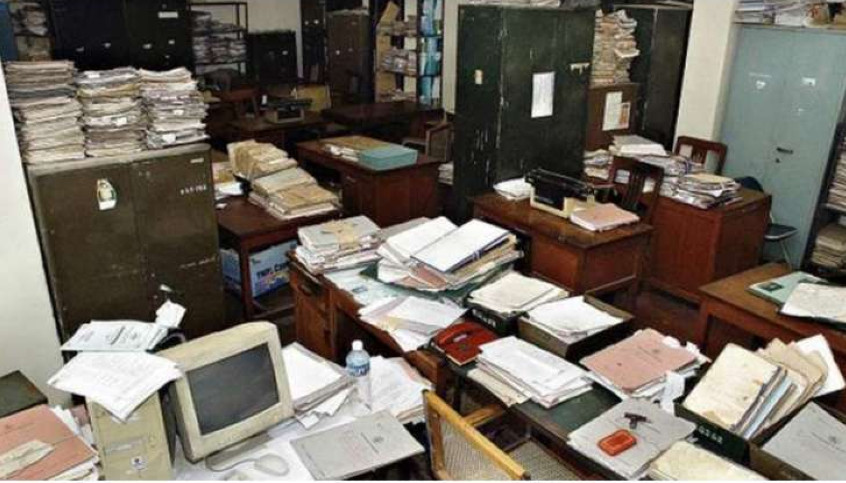

Why the System Keeps Failing

Flash floods may be triggered by climate, but their impact is magnified by policy and infrastructure failures:

Despite PDMA alerts, communication failures and public distrust prevent effective evacuations. Many people simply don’t believe or understand the risk.

In the Swat tragedy, the family waited over an hour for rescue—an eternity in a flash flood. Posts from @MarkusVerner and others criticized Pakistan’s inability to act, despite clear forecasts.

Flood-prone areas like riverside hotels in Swat remain unregulated. Drainage systems are outdated, and urban planning rarely includes climate resilience.

Reforestation, disaster drills, and sustainable urban development remain underfunded. The Mohmand Dam may help reduce flood risk, but broader action is urgently needed.

Human Toll and Economic Fallout

Flash floods hit the poorest communities the hardest:

-

In 2022, floods left 2.1 million homeless and triggered cholera, dengue, and other outbreaks.

-

In Swat (2025), 56 homes were damaged, 6 destroyed, and livelihoods in tourist towns like Bahrain and Kalam were disrupted.

Tourism, farming, and fishing—pillars of local economies—are increasingly fragile in a warming world.

The Swat River flash flood is not just a tragedy—it is a symbol of a country on the frontlines of climate change, struggling against forces it didn’t create. The drowned family from Sialkot, the helpless witnesses, and the delayed response reveal a broader truth: climate adaptation cannot wait.

Pakistan is living the climate crisis. The world must act—not just with words, but with funding, fairness, and urgency. Because next time, the flood may come faster, and the cost may be even higher.