In an elementary school on the outskirts of Dadu, the bell rings at 12:30 p.m. But the classroom is already vacant. Ten-year-old Azeem and his classmates left hours before, not due to tests or punishments, but because the heat was simply too unbearable.

The school becomes a furnace come mid-morning because there is no electricity, no fans, and hardly even drinking water. Azeem continues, "My eyes are burning and I'm about to faint," grasping a cracked bottle of lukewarm water. "We don't even get to sit on breaks."

This is not all about Dadu. Millions of children in Southern Punjab, Sindh, and parts of Balochistan are going to—or leaving—schools that are basically not viable for Pakistan's new climate.

As the temperatures soar

Pakistan is among the top ten nations in the world that are most exposed to climate change. Jacobabad, Dadu, and Bahawalpur each experienced over 20 days in 2025 when the temperature exceeded 48°C. UNICEF and WHO state that when temperatures exceed 40°C, children are much more likely to develop heatstroke, dehydration, and renal failure.

But these are the areas where schools lack even the most fundamental safety measures against intense heat.

A teacher in Dadu said, "The fan hasn't worked in two years." "We open the doors, but hot air comes in like fire."

During May and June, rural schools are heat traps when the mercury climbs over 45°C. This compromises children's right to education, health, and survival.

Pakistan is among the top 10 most climate-vulnerable countries globally. In 2025 alone, Jacobabad, Dadu, and Bahawalpur recorded over 20 days with temperatures exceeding 45°C. According to UNICEF and WHO, temperatures above 40°C significantly increase the risk of heatstroke, dehydration, and kidney failure in children.

Yet, these are the very districts where schools lack the most basic protections against extreme heat.

“The fan hasn’t worked for two years,” said a teacher in Dadu. “We open the doors, but hot air blows in like fire.”

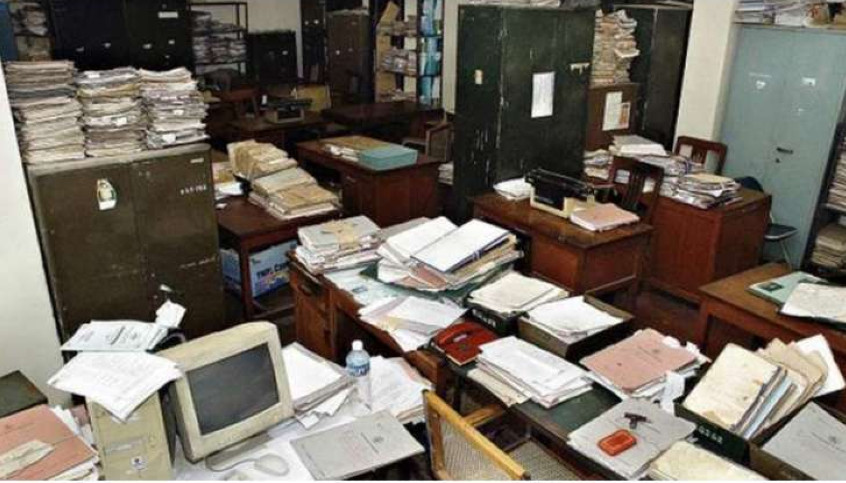

The Economic Survey of Pakistan 2025 presents a scathing indictment:

- 69% of public schools in Sindh lack electricity

- 43% have no toilets

- 42% lack access to drinking water

- 39% have no boundary walls

In Dadu and Jacobabad—two districts with record heat spikes—over 72% of government schools operate without electricity. In Bahawalpur, where 47°C has become the new normal in June, more than 60% of schools lack functional fans or water coolers.

And these are only the schools that remain open. Many shut down during peak summer months, not for planned vacations, but because continuing lessons becomes a health hazard.

Budget blues

Crucially, less than 10% of these funds are earmarked for infrastructure improvements—and almost none for climate adaptation (heat-resilient roofing, solar panels, water tanks, etc.).

“You can’t teach under a tin roof at 48°C,” says social worker Saleema Bano from Jacobabad. “It’s not just unjust. It’s dangerous.”

Toll on learning and lives

According to Alif Ailaan’s 2025 rural attendance survey:

- In areas experiencing 45°C+ days, student attendance dropped by 43%.

- Teachers reported an increase in fainting spells, vomiting, and absenteeism.

- Over 12% of rural female students dropped out permanently due to summer-related health issues.

Beyond academics, the mental toll is high. Children interviewed in Bahawalpur spoke of “fear of school” during heat spells. Parents are increasingly reluctant to send kids to unsafe schools, fearing health emergencies they cannot afford to treat.

The federal budget for 2025-26, presented on June 10, 2025, allocates Rs. 58 billion for Education Affairs and Services, a significant reduction from the Rs. 103.781 billion allocated in 2024-25. This represents approximately 0.33% of GDP, even lower than the 1.4% you mentioned, and well below UNESCO’s recommended 4% of GDP for education. The reduction has been criticized for limiting federal support for initiatives like the Higher Education Commission (HEC) and programs in federal territories like Islamabad and Gilgit-Baltistan.

Education is primarily a provincial responsibility under the 18th Amendment of 2010, and provinces allocate significant portions of their budgets to education. The figures you provided for provincial budgets are significantly lower than the latest reported allocations. Here are the corrected figures for 2025-26, based on available data:

- Punjab: Allocated Rs. 673 billion for education, approximately 17% of its total provincial budget of Rs. 4,000 billion. This is much higher than the Rs. 40.5 billion you cited. Punjab’s focus includes teacher training, school infrastructure, and scholarships.

- Sindh: Allocated Rs. 508 billion, around 15% of its total provincial budget of Rs. 3,400 billion, compared to the Rs. 32 billion you mentioned. Sindh emphasizes improving school facilities and addressing out-of-school children.

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP): Allocated Rs. 393 billion, roughly 22% of its total provincial budget of Rs. 1,800 billion, not Rs. 18 billion as stated. KP leads in education spending as a percentage of its budget, with investments in digital learning and vocational training.

- Balochistan: Allocated Rs. 162 billion, about 12% of its total provincial budget of Rs. 1,350 billion, higher than the Rs. 14.2 billion you noted. Balochistan struggles with infrastructure, with only 23% of primary schools having potable water.

“My son fainted twice this summer. We stopped sending him,” says Abdul Karim, a farmer in Dadu. “There is no water, no fan. Is this education or torture?”

“The water cooler was stolen. We told the district office, but they said no funds,” admits a school headmaster in Bahawalpur.

These voices are a haunting echo of a system that has failed its youngest citizens.

Despite clear warnings from climate scientists and NGOs, government action remains tepid. A proposed Rs. 2 billion solar school program in Sindh is still in its pilot phase. A National Climate Resilient Education Strategy was drafted in 2023 but remains unimplemented.

In the 2025-26 budget speech, education was mentioned only thrice, and climate adaptation in schools not at all.

To protect children and guarantee their right to education in a changing climate, the following urgent steps are needed:

In the face of climate emergency, Pakistan’s rural schoolchildren are among the most vulnerable. Their education, health, and dignity are being compromised daily by a toxic mix of heat and neglect. The crisis is visible. The solutions are known. What remains missing is the political will.

The next time the temperature rises above 45°C, and a child walks barefoot to a school without a fan or water, remember: this is not just a weather problem—it’s a moral one.